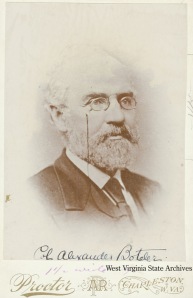

Shepherdstonians, jealous at the success of Robert Fulton, had talked of building a monument to Rumsey as early as the 1830’s, but it was Congressman A R Boteler, an early Rumsey advocate, who first took steps to do it. Around 1890 he began corresponding with the Norfolk and Western Railroad for the present Shepherdstown site, where the railroad had a small quarry. But Boteler died in 1892. After his death, the railroad built a new bridge downstream and the line shifted, leaving both a promontory overlooking the river and room for a community park.

Real efforts only began in 1900, likely spurred by New York’s preparations to celebrate Robert Fulton’s centennial. Local lawyer George Beltzhoover, Jr, local judge and poet Daniel Bedinger Lucas, and the West Virginia Historical Society eventually would prevail upon the WV legislature to make an initial grant in 1906. To see the project through, The Rumseyan Society ( with updated spelling of the name) was re-created, with Lucas its first President. The WV legislature slowly parceled out $13,625, over seven years, and the remainder of the $15,200 cost was raised locally. Finally, in 1913, with money at hand, the Forbes Granite Company of Chambersburg ( who had done the Indiana Monument at Antietam Battlefield) were hired to build it. Site preparation, concrete work and stonemasonry were overseen by J. Bittner, done by W. “Big Mustache” Jones and his crew.

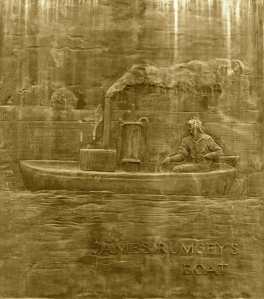

Though the monument itself was erected by March, 1916, landscaping, boundary stone walls, etc. took longer. The brass plaques arrived in August 1916. Beltzhoover was author of the text, which was enthusiastic, if not entirely scholarly ( Rumsey did not yet have a steamboat, in 1783) . Artistic license on the other plaque can also be seen in the representation of Rumsey’s steamboat as being about the size of a small rowing skiff, with a steam engine uncomfortably close to the lone boatman’s knees. A paved road was added in summer of 1917 and, accessible to automobiles, the park was done.

The Rumseyan Societ y donated the Monument and park to the town in 2007.

y donated the Monument and park to the town in 2007.

September 24th, 2015 at 7:58 AM

Visited the monument on Sept. 23, 2015. Such an impressive location! However, despite this being the 100th year of its dedication, it seems the town has allowed the area to become overgrown. Sumacs have invaded the lilacs, and a good pruning would greatly improve the spectacular view. Just sayin…

October 1st, 2015 at 12:41 PM

We’re just a historical society; the town owns the Park. The maintenance of it has been somewhat haphazard, we agree, but it’s also somewhat challenging- clearing away invasive vegetation from the river side involves essentially hanging onto a cliff.

May 9th, 2017 at 12:07 AM

[…] https://jamesrumsey.org/the-rumsey-monument/ […]

September 20th, 2022 at 8:44 AM

I’m a storyteller (born in MD, now retired in Tampa FL) and are interested in submitting a proposal about James Rumsey for the 2023 the Speak Stories program in Shepherdstown.

Since 2008 I have written and told several hundred stories under the identity “The Story of Industrial America” and would very much like to share the story of James Rumsey’s life and accomplishments with the world.

Curious (from the Society’s point of view) about how aware people are, of his contributions?

September 25th, 2022 at 10:25 AM

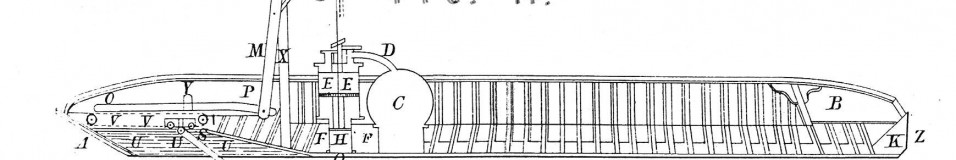

I would say that for most of the US, if Rumsey is known at all it’s as a failed steamboat inventor. From the earlier 19th up until this century ( after we added an exhibit to the Museum and demonstrated the steamboat replica) Shepherdstown would have known him as the unjustly unrecognized inventor of the steamboat. Both of these are not really correct. Rumsey’s ideas were not at all limited to steamboats. And neither his steamboat or John Fitch’s, his rival, could be called THE steamboat- they were completely different, and different from Fulton’s. With lawyerly and hopeful language Virginia patriots tried to assert that Rumsey’s boat had successfully operated much earlier than Rumsey himself claimed, and everyone ignored a lot of the interesting other ideas he had, for power hydraulics and hydraulic turbines.

But that ignorance unfortunately is rather important, for people who want to tell a typical heroic story of invention and the advance of technology. When Rumsey died in 1792, his designs were almost all just on paper. There was a test turbine powered mill in Pennsylvania that soon vanished from the records, a steam-powered jet boat in London that was almost certainly broken up for scrap, an over-turned boat hull in a mill pond in Shepherdstown, and a likely a pile of personal papers in his rooms that were dispersed by the time his executor arrived from the US to look for them. His contributions could have been significant, if anyone had looked at his patents, but they didn’t. I’ve done talks before, showing images of some of his designs, explaining the story, but for people used to the happy gosh-isn’t-it-wonderful plots of popular series like How I Built This, I don’t think the narrative is very satisfying. It was not a story of villains vs heroes ( Fitch vs Rumsey) and it was not a story of superior technology displacing inferior technology. The protagonist did not die wealthy at the peak of his success, or even surrounded by his friends. He may have battled adversity, but never overcame it. It’s diverting for tech geeks to look at his gradual creation of a true, advanced hydraulic turbine- but most people’s eyes glaze over.

However, if you’re looking for local grist for your mill, you might look into the Potomac Canal, a project started by Washington in 1785 that briefly involved Rumsey as engineer. The company tried to do everything on the cheap- avoiding digging a canal when they could use the river, not importing a real engineer from England where they knew how to do such things. The result was something that couldn’t be used for boat traffic many times during the year, being subject to spring floods, summer droughts, and winter freezes. It kept going broke, until eventually it was absorbed into the C&O Canal. However, engineers often say that failure is more informative than success, and its failure was indeed useful: when the projectors in New York began to plan the Erie Canal, they were able to learn from the example of the Potomac Canal and so avoid using the seemingly-convenient Mohawk river. If the Potomac Canal had an effect on the Erie, the Erie Canal then had great effects on the farms of the east. When the large farms of the midwest were able to ship their grain by boat to New York, the price dropped all along the coast, and it became less profitable for farmers of the Shenandoah Valley to send their harvest north, by wagon- especially through Shepherdstown, which depended on that traffic. The result was a depression in Shepherdstown: which is why so many old buildings survive in it now, and give it character.

Kapsch’s The Potomac Canal is a good source for that project, as is Bernstein’s Wedding of the Waters for the Erie.