Below, the rotary engine from Rumsey’s 1791 English patent. Like most of his designs, it was never built. The first view is the engine from above. The rotor in the middle spins around, within a hollow case, and the large cams NN alternately push out and let drop the gate valves that are connected to the rollers, R. Yes, this is mysterious. Look at the next drawing, below it.

Fig. 13, below. Engine from the top, with the top plate MM off. Steam flows in through the axle and out into the turbine arms- DD. It expands in the space between the semi-circular rotor seals and the gates, EE, pushing the rotor around. As the rotor turns, gates are lifted and closed, creating two “strokes”: 1) a gate closes behind a steam port on the rotor , steam is admitted and expands, turning the rotor. 2) the next gate is closed behind the steam port: the parcel of steam ceases to expand . 3) another gate opens, allowing the parcel of steam into one of the exhaust ports in the rotor , out through one of the exhaust arms, BB, and then out the hollow axle. With an air pump, pumping out the condenser, there would be significant vacuum in the exhaust port. With two intake and two exhaust ports, there are two expansion strokes, and two condensation strokes, per revolution.

Note that, with three gates 120 degrees apart and two ports 180 degrees apart, there is always a closed gate between a steam port and an exhaust port. He could have designed it with one set of ports and two gates: that would have been more efficient ( note that , at the top of Fig.13, there is a parcel of steam sitting between two gates, doing no work). But two sets of ports in effect creates two “pistons”, giving twice as much torque as one set.

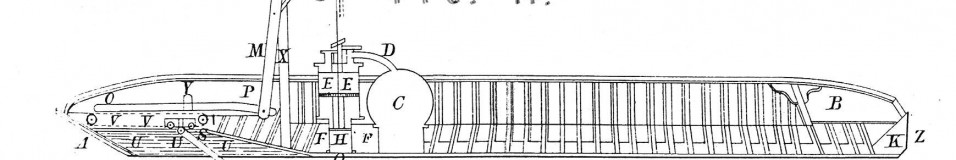

Fig. 12. The engine from the side. Steam flows in from the top ( through a rotating seal UU) and into the hollow turbine arms DD and then into the turbine, where it expands. The condensed steam drains through the other hollow turbine arms H and is pumped out by the gear pump LL at the bottom into the “hot well”, or water reservoir, V. Rumsey’s drawing of the rotor and casing is over-simplified here, not clearly showing the case or the top and bottom plates. The letters a,b,c,d are described as “a ring of metal” to hold the “ocum”, or seal packing, in place: these would turn with the rotor.

Fig. 12. The engine from the side. Steam flows in from the top ( through a rotating seal UU) and into the hollow turbine arms DD and then into the turbine, where it expands. The condensed steam drains through the other hollow turbine arms H and is pumped out by the gear pump LL at the bottom into the “hot well”, or water reservoir, V. Rumsey’s drawing of the rotor and casing is over-simplified here, not clearly showing the case or the top and bottom plates. The letters a,b,c,d are described as “a ring of metal” to hold the “ocum”, or seal packing, in place: these would turn with the rotor.

Though no mechanical linkages, grindstones, etc. are shown, clearly Rumsey thought of this as an industrial engine, for a mill; like the hydraulic turbines it vaguely resembles.

August 7th, 2011 at 2:50 PM

Thank you for this wonderful piece of history and enlightenment. My cousin, Frances Skiles Gilfillan, did a genealogy of the Skiles’ family in 2007. Included in it to my delight was our James Rumsey, his daughter Edna Susan Rumsey and grandson James Rumsey Skiles, son of Jacob Skiles and Edna. Recounted from Warren County Kentucky History: are the accounts of James Rumsey, INVENTOR of the steamboat and whom George Washington encouraged to bring his vessel for demonstration on the Potomac River in 1787, a full twenty years before Robert Fulton constructed the Clermont. In fact, Robert Fulton was James Rumsey’s apprentice and took credit for the invention after Mr. Rumsey’s untimely death in England while promoting his steamboat there.

March 22nd, 2012 at 10:05 AM

The evidence that Fulton got his ideas from Rumsey is very circumstantial- at best, they seem to have known each other. But Fulton did not work under Rumsey, and their designs have little or nothing in common. Rumsey expressed a dislike of paddlewheels for propulsion ( after Symington put one on his steamboat) and Fulton used one. Rumsey went to great lengths to create a compact but overly-elaborate steam engine, unlike any others, for his last steamboat, Fulton simply asked Boulton and Watt to supply him with one of their engines to fit his boat. Symington’s success may have inspired Fulton more than Rumsey.