The steamboat is so pretty, why don’t you run it? And while you’re at it , take me for a ride?

Most people who went for a ride with us spent a lot of time waiting for us to go…

Bill Hunley gave us a great design for the hull, and it really does look like it should be on the water, chugging around. But even launching the boat is a major undertaking, and the engine is too unreliable, too under-powered, and too exhausting to run for fun. Since we couldn’t change it into something else, after 20 years we had to stop. We were tired!

We are trying to come up with a Rumsey steamboat that’s more fun, using his rotary engine design. He never built it, so we have more flexibility with the details of this project.

Why do we hear about Robert Fulton, but not James Rumsey?

Fulton was successful with his steamboat, Rumsey was not. It wasn’t just because Fulton’s boat was better; with a bit of development Rumsey’s would have worked well enough, and his was not the only one. There were at least eight steamboats proposed before Fulton’s 1807 debut. Some were built, a couple worked quite well , and none were a financial success. Fulton could indeed import a state-of-the-art Boulton & Watt engine from England for his boat, which saved him much time and trouble. But his most significant advantages over the previous inventors were not technological; he was well-connected politically and socially, had a good amount of his own money and had the strong financial backing of the richest man in New York, Robert Livingston. He also knew that a steamboat didn’t just have to fill a need; it needed to have a good market, and he chose to set up operations on the Hudson, a very good river on which to run a passenger boat, where sheer banks and hilly terrain hindered competition from coaches.

Think of Fulton as being a little like Henry Ford; Ford really brought the automobile into the world as a standard form of transportation, Fulton did the same for the steamboat.

Did Fulton ever meet Rumsey?

They were both in England around the same time and were both friends of Benjamin West, so they likely knew of each other. Fulton was indeed quick to take other people’s ideas when it suited him, and before building his own, he doubtless researched Rumsey’ s as well as John Fitch’s and William Symington’s boats, perhaps also Jouffroy d’Abbans’ in France. But there’s no evidence that Fulton worked for Rumsey. Fulton’s steamboat, once built, had really none of Rumsey’s steamboat in it, either. With Symington, though, it’s another matter. Symington’s 1788 steamboat had both a paddlewheel and a modern steam engine, and ran quite successfully, and was well-known ( even Rumsey commented on it – negatively- he thought jet propulsion was better). Fulton’s boat also had a modern steam engine and a paddlewheel, like Symington’s, and even Matthew Boulton noted that the engine Fulton had ordered from his company was identical to Symington’s in the important dimensions.

Still, by the 1830’s, the legend in Shepherdstown was that Fulton had gotten his ideas from Rumsey. In the three decades after Rumsey’s death, Shepherdstown changed his story from one of simple tragedy ( an inventor dying early , before his ideas are brought to fruition)- to one of tragedy and injustice- ( an inventor dying early, his work successful but unnoticed, and his profitable steamboat idea stolen by others). It was only Ella May Turner’s biography of him that dispensed with the folklore.

Was Rumsey’s the first steamboat?

There are so many words that have been wasted over this seemingly simple sentence! It was not just Shepherdstown’s oral tradition that made steamboat history a partisan matter , the steamboat itself really began that way. Rumsey had a rival, John Fitch. The affair is complex, but it does not really fit the popular plot of hero vs. villain. Telling it could fill a book: we’ll try limit it to a few careful paragraphs, here.

Rumsey showed George Washington a model of a mechanical poleboat in the fall of 1784 and got his endorsement. Encouraged, he also talked to Washington about putting steam power on the boat as well. Over the next several months, Rumsey took advantage of Washington’s endorsement and got a somewhat vague patent from the Virginia legislature on his boat. In March of 1785 he wrote George Washington to say he’d completed his plan for his steam- and poleboat. Employed by the Potomack Company that summer, Rumsey also had the money finally to build, and began building that fall.

Fitch said later that he’d thought of making steam power a boat in the spring of 1785. He then began travelling through the states, fundraising for a company to build his steamboat the following summer. A company was formed, and he began building sometime the following winter. After great difficulty he demonstrated his steamboat in Philadelphia, in August of 1787.

Rumsey had had reverses in his project- losing his position with the Potomack Company in the summer of 1786 deprived him of funds, and development of the boat stopped for months. Hearing of Fitch’s demonstration and knowing that a successful Fitch could take all his steamboat designs, Rumsey borrowed heavily and was able to have his first public demonstration on December 3rd, 1787 in Shepherdstown, three months after Fitch’s. Rumsey advocates have often claimed he had a working steamboat earlier than this , by interpreting his 1786 river trials in a very hopeful way. Rumsey also cast those trials in a somewhat hopeful light; but he himself never claimed his steamboat actually worked before Dec.3rd ( his pamphlet detailing those claims even included affadavits from witnesses who said the steamboat machinery was “incomplete” on Dec. 3rd). So, if you wish to think of it as a race and want to know who crossed the finish line first, Rumsey himself would have said, John Fitch.

Rumsey would have also said, however, that the dispute was not about a race; it was about owning his ideas. Fitch had obtained broad monopoly patents from several states that gave him rights to his own and any other steamboat, once he had a working steamboat of his own . A monopoly offered investors a safer bet, and it was not unheard of for a government to grant one to boost a project: but it was typically for something completely new. Rumsey’s claim was that , since he’d started building before Fitch, and because his design was completely his own and unlike Fitch’s, it was unfair to give Fitch the rights to it just because Fitch had built his own boat. But though George Washington had told Fitch of Rumsey quite early on, in the fall of 1785 ( and had told Rumsey of Fitch, as well), Fitch claimed Rumsey was a spoiler, who labored in secret and emerged late to upset Fitch’s project just when he was about to reap the monopoly he deserved- and to which some states had already agreed. Because Fitch felt he had the law firmly on his side to do what he liked with Rumsey’s ideas, and Rumsey valued all his intellectual property very highly , arbitration efforts by Philadelphia businessmen to create a joint venture failed.

The dispute was finally adjudicated a few years later, in 1791, when a patent system was created for the entire ( and recently formed) United States . New and inexperienced, and perhaps distracted by other worries ( one member, Thomas Jefferson , was serving as Secretary of State) the patent commission awarded both inventors ill-defined and overlapping design patents that clarified little about their rights. Fitch felt the Commission had been stacked with Virginians, who sided with the Virginian Rumsey. There could have been a bias ( all the records of the Commission burned in the great Patent Office fire of 1839, so it is hard to say). But Rumsey himself was equally furious with the result, so both inventors felt they’d lost. He had gone overseas to England early in the dispute; the patent decision contributed to his decision to stay there, where he died in December 1792. After being denied both his monopoly and a real patent, Fitch abandoned his steamboat work in Philadelphia, and eventually died , destitute, in Kentucky about five years after Rumsey. Historian Brooke Hindle has said the botched patent ruling was instrumental in halting steamboat development in the US for the next twenty years.

Most sources for the Fitch/Rumsey dispute are partial, biased, or completely missing. Fitch, for example, left a detailed and captivating memoir, which is the sole surviving source for some important events, like the Patent Commission Hearing of 1791 ( again, that Patent Office fire in 1836 largely wiped out all internal documents of their case) . With his very complete story, Fitch is easier to write about. But his complete narrative is also biased, written in part to settle scores with the many people Fitch felt had treated him unfairly. Whatever similar papers Rumsey might have written vanished with his death, and his few letters contain little or no biographical information. With much less of Rumsey’s side of the story to use, Fitch has gotten more attention from authors, Rumsey less. And, once Fitch and his company had a steamboat, they tried to run it, and versions of it, for a few years. Rumsey’s steamboat was not run for very long, perhaps only weeks.

What ever happened to Rumsey’s steamboat, after 1787?

After two demonstrations in public in December, Rumsey pulled the machinery off the boat and in March of 1788 sent it to Philadelphia, to begin his dispute with Fitch. Fitch visited Shepherdstown in May of 1789, and found the hull of the boat upside down in a pond, abandoned ( this visit by Fitch would, in later years, be reworked by Shepherdstown oral tradition as happening five years earlier, with Fitch actually spying on Rumsey’s work). The boat engine almost certainly stayed with the Rumseian Society in Philadelphia, but very likely sometime after Rumsey’s death in December of 1792, it was disposed of, likely sold for scrap…though some smaller pieces might have been kept as souvenirs. Of these, the sole possible survivor is a length of chain acquired by Alexander Boteler likely sometime in the 1850’s and donated to the Smithsonian in 1866 . It’s well-made, well-finished machine chain that is far too good for mundane purposes and could well have connected a working beam to an air pump or steam cylinder. Boteler also had a fragment of iron pot, which supposedly Rumsey used in his 1785 engine boiler , the boiler which Rumsey quickly discarded as inadequate. Boteler donated the scrap to the Franklin Institute, but has now disappeared. Admittedly, it didn’t much look like an artifact a museum would want to keep.

Did Rumsey build another steamboat?

Yes, in England. It was called The Columbian Maid, another jet boat. We don’t know too much about it, but if it had the engine pump shown in Rumsey’s 1790 patent, it would have been complicated and difficult to make, and Rumsey died in December of 1792, before it could be finished. The Gentleman’s Magazine reported that it ran on the Thames the following February, and made four knots. But nothing more is known of what became of it; likely it was simply sold off by Rumsey’s partners and creditors, perhaps just for scrap metal.

July 8th, 2012 at 1:29 PM

I was just reading about the tugboat “Rumsey” which was “accoutred for running the Rebel batteris at Vicksburg” in Harper’s Weekly, May 30, 1863. I found references to a stern wheel steamboat named “John Rumsey” built in 1859 captained by Nathaniel Harris and Joseph Biggs (in 1863). Is this tug related at all to James Rumsey? http://www.sonofthesouth.net/leefoundation/civil-war/1863/vicksburg-blockade-runner.htm

July 11th, 2012 at 8:52 PM

I don’t have any knowledge of a John Rumsey. James Rumsey’s two daughters, his deaf-mute son, and at least one of his brothers, Edward, moved to Kentucky after James’ death, and they and their families got to see steamboats become the most important commercial transport in the South. A grandson, James Rumsey Skiles, did a lot to develop Hopkinsville, and even founded a town, which he named Rumsey, in honor of James. The family tried to get material compensation for James’ work from Congress, submitting a memorial in 1839- which was rejected in 1848 ( like many memorials). But, anyway, there were a fair number of Kentuckians , if not others on the Mississippi , who would still know the story and like the name put on a steamboat in the 1860’s. Any notion where the tug was from?

That it was a Union boat is interesting. By the 1830’s, there was a belief in Shepherdstown that James had had a working boat sometime in 1785, if not earlier, and that both Fulton and Fitch had stolen the idea of a steamboat from him . As stated elsewhere in this blog, neither Fulton’s or Fitch’s designs owed anything to Rumsey’s, so really the most that could be claimed is they heard something about him. But the political strife of the next few decades added a patriotic edge to the question. When A.R. Boteler ( later Confederate colonel and congressman) began to write about Rumsey, in the 1850’s, he had an evident pride in Rumsey being a Virginian ( “to Virginia belongs the honor…”). Fulton and Fitch were both Yankees. Putting the name Rumsey on a steamboat in the war, you might think, could have been thought to be a Southern poke in the Northern eye. But apparently not here.

July 12th, 2012 at 1:48 PM

Thank you! You make some very interesting points. I will do a little more digging around. What I thought was interesting was that there was so little additional information about the tug in the article. Almost as if everyone knew about this steamboat. It may require more investigation …

Thanks again!

September 29th, 2012 at 4:48 PM

My maiden name is Rumsey and I grew up hearing that we are related to James Rumsey. My father, John Rumsey, grew up in West Virginia before his family moved to Washington DC. at some point during the first half of the 20th century. I’ve tried tracing my lineage through Ancestry.com to see if my family is indeed related to James Rumsey, but have been unsuccessful. Does anyone know how I might find out, once and for all, if I am a descendant of James Rumsey? Thanks for any and all help!

October 2nd, 2012 at 2:16 PM

James Rumsey himself had no male descendants, his brother Edward had quite a few and moved to Kentucky. We have not worked up a geneology of the Rumsey family, and consider it a low priority. However, we do have a file that we keep on the family, welcome additions to it. If you can track your family back to a Rumsey circa 1850, we might have something. But most of the file is earlier than that.

Nick B.

January 13th, 2013 at 8:16 PM

Rumsey wrote his brother Edward in March 1789 and said, “a gentleman here has undertaken to furnish me with a vessel to try my experiment upon. She is now building at Dover, 72 miles from London. She is large enough to go to the East Indies. The engine is making for her and I expect to make the trial in May”. In a later letter from London he described the ship as being “burthen 101 and 45/95 tons”, but though another letter, to Th. Jefferson, was posted from Dover no shipbuilder’s name in either of these is mentioned, nor does it appear elsewhere in Rumsey’s few surviving letters.

August 31st, 2016 at 3:35 PM

I’m related to him as well. My great grandfather was named James Rumsey Crenshaw. It’s complicated to try to explain, but I’ve traced it back via ancestry.com and it checks out.

October 29th, 2016 at 9:12 AM

Howdy,

Sorry for the late response.

We don’t concentrate on geneology, unlike many historical societies, but we do get inquiries and so have a file on the Rumsey family and welcome additions to it. There’s fairly little on family members past 1850, especially those not descended from James’ brother Edward, who had many children. If you have a spare moment and would like to send us what you’ve found, we’d be grateful. You can email it here, or post it to The Rumseian Society PO Box 1787 Shepherdstown, WV 25443.

many thanks

Nick Blanton

November 29th, 2020 at 9:18 PM

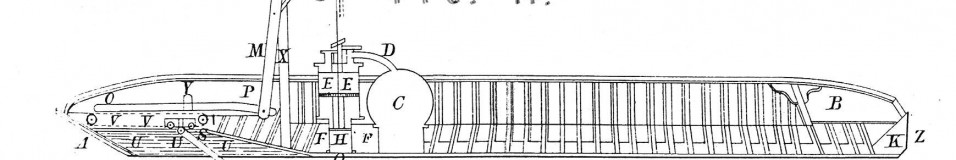

I am assembling a book, to be entitled “Chronicles of Mechanical Engineering.” It will include an article about the efforts of James Rumsey, and especially his steam boat. I love the illustration you have on this website on how the steam engine functioned. May I use that image in the book? I would, of course, credit its source.

Thanks in advance for your consideration,

Tom Fehring

ASME History and Heritage Committee

Immediate Past Chair

November 30th, 2020 at 10:49 AM

Sure. Pleasant to learn that ASME has a History and Heritage Committee!

Drop me a line at blantonnick@yahoo.com and I can send two JPG’s- not very big ones, but perhaps better to use than copying the ones of the site.

Credit would be nice, of course. The artist of the original released rights to us but wanted the surprised fish ( lower left) to be retained when we re-did the drawing for the museum, and she would likely prefer it be retained in your book.

September 1st, 2022 at 12:48 PM

Have you all encountered this history relating to James Rumsey? Same James? Always amazed that people moved around mid-18th C. America. West Va. is a long way from SE Louisiana. But then Lewis and Clark walked a bit.

https://donaldsharphistory.blogspot.com/2018/12/the-secret-of-pearl-river-island.html

September 2nd, 2022 at 2:02 PM

We know Rumsey came with the rest of his family from tidewater Maryland to what was then western Virginia, in search of land- the family plantation had reached its limits of heirs. Likely date for that would have been around 1760, when the end of the French and Indian War promised the opening of new lands to the west. That opening didn’t happen, and the fact that Rumsey and his siblings married some of the locals and started families suggests they didn’t do any wanderings far afield before 1781, when he and a local business partner began trying to interest the Continental Congress in his paddlewheel-powered pole boat.

However, there was a Louisiana James Rumsey that gets a mention in the Oliver Pollock Papers, now at the Library of Congress. This Rumsey wrote a few letters to Pollock in the late 1770’s . Pollock had acted as broker and hired out some of Rumsey’s slaves to someone, that someone had treated them very badly, and while trying to be polite ( Pollock was a very important man) Rumsey is obviously very angry. It’s not the steamboat Rumsey: the handwriting and signatures are quite different. But as we don’t have letters or anything of steamboat Rumsey in this period, at least one researcher in the 19th c. thought perhaps they were the same.

We’re flattered he links to our site. But I am not sure what sources Don Sharp is using for his idea of Rumsey building his steamboat down in LA., and I don’t think I have heard from him on the subject. It is a bit of a stretch. Why would James Rumsey be going through years of trial and error and experimentation on the Potomac, if he had already gone through that process years before in Louisiana to build the same steamboat? And why would he write to George Washington in April of 1785, saying that since meeting him in the fall of 1784, he had been figuring out how steam propulsion would be added to the planned paddlewheel-powered poleboat- why wouldn’t he note that he had build a steamboat once before? Lastly, when embroiled in the patent fight with John Fitch in 1788, why wouldn’t Rumsey bring forward any evidence he’d already built a steamboat in Louisiana? It would have been incredibly useful, a crushing counterargument to Fitch’s claims of being the first to build a steamboat, at a time when Rumsey’s entire project was at risk of being appropriated by him.